Social Media Disinformation

Social Media & Threats, OCTOBER 13, 2020, By Small Business Administration Staff

Social media enables people to communicate, share, and seek information at an accelerated rate. In recent years, social media became the pinnacle of news consumption through its rapid dissemination, low costs, and its accessibility to consumers worldwide.[1] Often breaking and sensitive news is first made available on social media. Whether the information is fact-checked or not, it disseminates around the globe within minutes. Social media provides users the ability to exchange thoughts and ideas with people from corners of the worlds they might not have visited, enables strangers to collaborate and positively impact our collective society, and increase awareness to help grow our businesses and communities. However, social media is a double-edged sword, for all the good we intend to accomplish, social media is also an adversary breeding ground for subverting social media use for their illicit gain.

In this blog, the United States Small Business Administration (SBA) Cybersecurity team members explain common social media risks posed by misinformation campaigns, phishing and scams, malware, and account takeovers. Along with tips to protect businesses, home networks, and individuals.

Social Media Misinformation Campaigns and Measures to Fact-Check (Elizabeth Iskow, Cyber Threat Intelligence )

Quick dissemination and viral posts allow adversaries to spread misinformation and “fake news” through deepfake accounts, bots, big data, and trolls to create circumstances to benefit their agendas.[2] Misinformation campaigns are stories presented as if they are legitimate.[3] In 2016, “fake news” emanated on social media as the deliberate presentation of typically misleading or false news claims.[4] Deepfakes evolved the past couple of years as a subset of Artificial Intelligence (AI) that leverages neural networks to manipulate videos and photos while maintaining an authentic presence.[5]

Adversaries treat social media as a golden opportunity to spread malware to unsuspecting individuals. Links from untrusted or unsolicited social media accounts, profiles, and messages can be boobytrapped to deliver malware to your devices. As such, malware poses a serious threat that homes, businesses, and individuals.

Account Takeovers can result in losing control of accounts from Email, Social Media, Banking, etc. The key to taking over these accounts is commonly through your most popular form of online identity, your email address. To protect against account takeovers, ensure that your Email and Social Media accounts have extra precautions in place, such as MFA.

A Guide to Misinformation: How to Spot and Combat Fake News, Verizon

Unfortunately, there is a dark side to social media: fake news. Misinformation can influence users, manipulating them for political or economic reasons. How can you spot fake news, and what can you do to combat it? This guide will provide a comprehensive view of the subject and give you the tools you’ll need to address this burgeoning issue.

Often referred to as “fake news” in modern times, the term “misinformation” is defined as false or inaccurate information that may be distributed with the intent to deceive those who read it.

Information or opinions that you disagree with may not necessarily constitute misinformation. While the term “fake news” is often used as a pejorative in journalism today, this is a dishonest use of the term; indeed, the practice of calling fact-based reporting “misinformation” based on the premise that it doesn’t align with your political views could arguably be called misinformation itself.

Misinformation vs. Disinformation

While the two terms are commonly used in place of one another, “misinformation” and “disinformation” are not synonyms. Misinformation refers to inaccurate reporting that stems from inaccuracies; as such, the term does not imply an intent to deceive. Disinformation, on the other hand. refers to the intentional spread of inaccurate information with the intent to deceive.

Misinformation on Social Media

In addition to making sure to never share personal details on social media, it’s important to understand the impacts of sharing potential misinformation. This can take on many different forms, and each can have a negative impact on public discourse by misleading and manipulating readers — whether intentionally or not.

Reliable News Sources

The most reliable news sources produce news content by following rigorous journalistic standards and focusing on fact-based reporting. News sources, such as The Economist, Reuters, National Public Radio, and The Guardian are some examples of widely- and highly-trusted publications.

How Social Media Companies Are Combating Misinformation

As you can see, there are many unreliable news sources and different types of misinformation. As a result, social media companies have taken action to combat it.

Facebook has recognized the problems associated with fake news and is taking action to address it. Some initiatives in this vein include the Facebook Journalism Project and the News Integrity Initiative. These are designed to spread awareness about the problems associated with fake news, as well as increase overall trust in journalism.

Facebook has also vowed to label or remove fake news as the presidential election draws closer in an effort to minimize the influence of politically motivated fake news. The company has taken action against individuals and pages sharing fake news, removing them from the site when appropriate.

Twitter has clearly stated its stance on misinformation:

We, as a company, should not be the arbiter of truth. Journalists, experts and engaged citizens Tweet side-by-side correcting and challenging public discourse in seconds. These vital interactions happen on Twitter every day, and we’re working to ensure we are surfacing the highest quality and most relevant content and context first.”

In short, the platform does not seek to combat misinformation directly. It does, however, take action against spammy or manipulative behaviors, particularly when it comes to bots. Indeed, millions of accounts have been suspended for this reason.

How to Recognize Fake News and Misinformation

How can you recognize misinformation on social media? It often has a clear bias, and it may attempt to inspire anger or other strong feelings from the reader. Such content may come from a news source that is completely unfamiliar, and the news itself may be downright nonsensical.

Once you’ve spotted a suspicious piece of content, look into the publisher and author of the content. Do either have an established reputation? Are they known as trustworthy sources? If not, do they cite their sources — and are those reputable?

Fake news often uses fake author names and bogus sources. If the site has a history of making suspicious claims, or details in the author bio don’t seem credible (or a bio is non-existent), you should treat the content with extreme scrutiny. Check out the site’s “About Us” page for information about the publication. You may notice suspicious details. Cross-reference these details with reputable news sources to determine the authenticity of their claims.

The “About Us” section of the site may even blatantly label itself as parody or satire. For example, one publication that is commonly misinterpreted as a legitimate news site, The Onion, blatantly states, “The Onion uses invented names in all of its stories, except in cases where public figures are being satirized.

In addition to following the above considerations, there are many telltale signs of a fake news story to be on the lookout for:

-

Faked website address: An article may claim to be from a well-known news publication, but is the web address right? Compare the web address to the home page of the actual news organization in question. If there are discrepancies or misspellings in the address, you may have spotted a fake.

-

The author is anonymous (or extremely well-known): Fraudulent publishers may use a generic author name or omit the byline entirely in order to avoid scrutiny. Alternatively, they may use a very famous person’s name as the byline. The latter warrants investigation. Is it truly possible, for example, that Neil deGrasse Tyson would write an article claiming that the Earth is flat? If so, would he have published his claims on a website that has no reputation whatsoever? In such instances, exercise a healthy amount of skepticism.

-

The article misrepresents or misquotes its sources: Citing reputable sources is an effective way of making your argument seem more credible. However, if the article doesn’t accurately reflect the sources it uses, it should be treated with suspicion.

-

The article contains spelling and grammatical errors: Real news sources employ editors to provide high-quality content. Purveyors of fake news often don’t. As a result, fake news articles may contain excessive writing errors.

Social Media and the Public Interest, Media Regulation in the Disinformation Age, by Philip M. Napoli

Mark Zuckerberg put it bluntly in his testimony before Congress: "We didn't take a broad enough view of our responsibility, and that was a big mistake."

Facebook, a platform created by undergraduates in a Harvard dorm room, has transformed the ways millions of people consume news, understand the world, and participate in the political process. Despite taking on many of journalism’s traditional roles, Facebook and other platforms, such as Twitter and Google, have presented themselves as tech companies—and therefore not subject to the same regulations and ethical codes as conventional media organizations. Challenging such superficial distinctions, Philip M. Napoli offers a timely and persuasive case for understanding and governing social media as news media, with a fundamental obligation to serve the public interest.

Social Media and the Public Interest explores how and why social media platforms became so central to news consumption and distribution as they met many of the challenges of finding information—and audiences—online. Napoli illustrates the implications of a system in which coders and engineers drive out journalists and editors as the gatekeepers who determine media content. He argues that a social media–driven news ecosystem represents a case of market failure in what he calls the algorithmic marketplace of ideas. To respond, we need to rethink fundamental elements of media governance based on a revitalized concept of the public interest. A compelling examination of the intersection of social media and journalism, Social Media and the Public Interest offers valuable insights for the democratic governance of today’s most influential shapers of news.

Combating disinformation in a social media age

The creation, dissemination, and consumption of disinformation and fabricated content on social media is a growing concern, especially with the ease of access to such sources, and the lack of awareness of the existence of such false information. We introduce different forms of disinformation, discuss factors related to the spread of disinformation, elaborate on the inherent challenges in detecting disinformation, and show some approaches to mitigating disinformation via education, research, and collaboration.

THE GLOBAL ORGANIZATION OF SOCIAL MEDIA DISINFORMATION CAMPAIGNS

Samantha Bradshaw and Philip N. Howard

Abstract: Social media has emerged as a powerful tool for political engagement and expression. However, state actors are increasingly leveraging these platforms to spread computational propaganda and disinformation during critical moments of public life. These actions serve to nudge public opinion. set political or media agendas, censor freedom of speech, or control the flow of information online. Drawing on data collected from the Computational Propaganda Project's 2017 investigation into the global organization of social media manipulation, we examine how governments and political parties around the world are using social media to shape public attitudes, opinions, and discourses at home and abroad. We demonstrate the global nature of this phenomenon, comparatively assessing the organizational capacity and form these actors assume, and discuss the consequences for the future of power and democracy.

he manipulation of public opinion via social media platforms has emerged as a to this problem: junk news is spreading like wildfire via social media platforms during key episodes in public life, bots are amplifying opinions at the fringe of the political spectrum, nationalistic trolls are harassing individuals to suppress speech online, the financial model that supports high-quality news and journalism is facing increasing competition from social media advertising, strategic data leaks targeting political campaigns are undermining the credibility of world leaders and democratic institutions, and the lack of transparency around how social media firms operate is making regulatory interventions difficult. Evidence is beginning to illuminate the global impact of the darker side of political communication. including disinformation campaigns, negative campaigning, and information operations.

SUSPECTED IRANIAN INFLUENCE OPERATION

Leveraging Inauthentic News Sites and Social

Media Aimed at U.S., U.K., Other Audiences

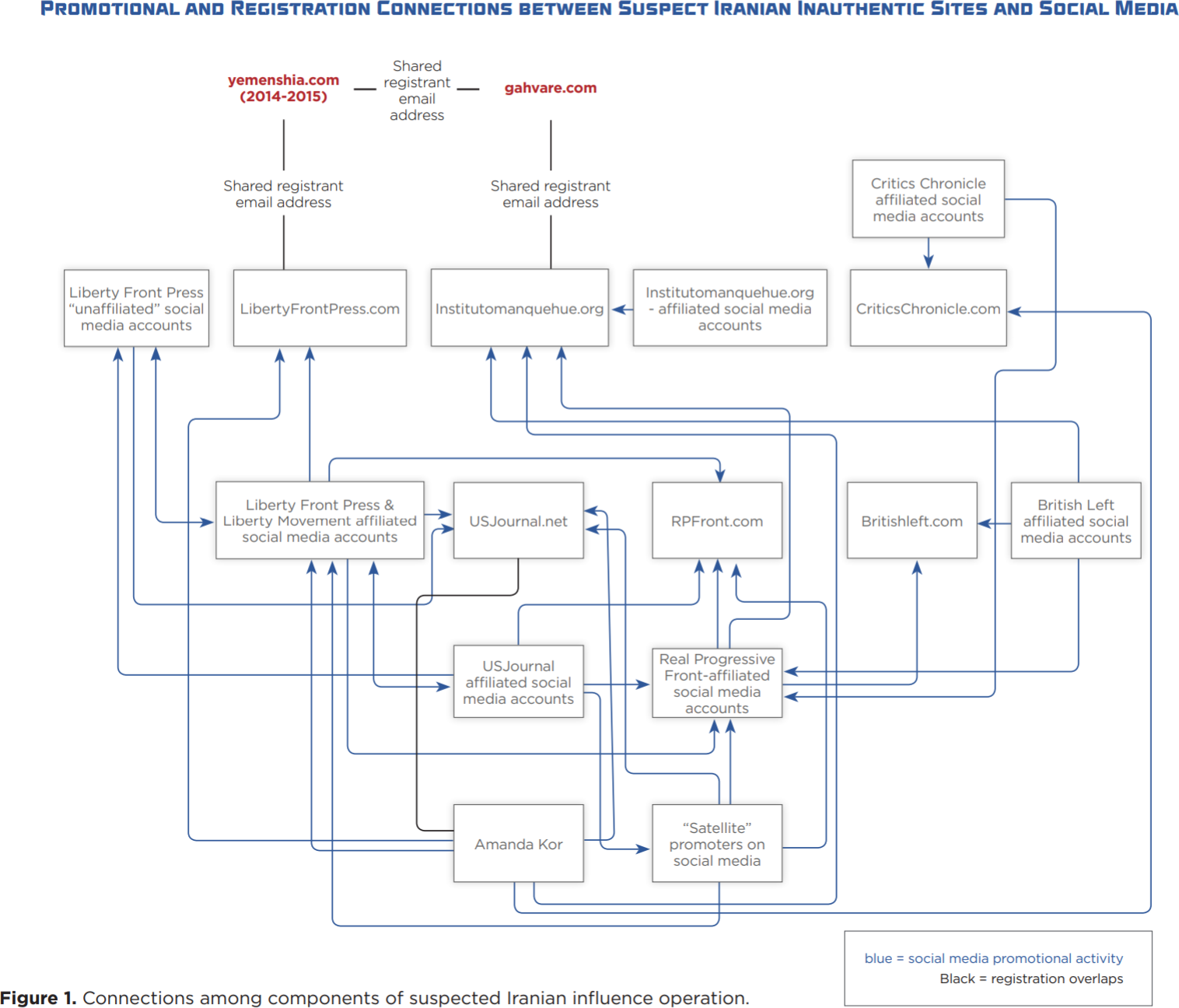

What Is This Activity? Figure 1 maps the registration and content promotion connections between the various inauthentic news sites and social media account clusters we have identified thus far. This activity dates back to at least 2017. At the time of publication of this blog, we continue to investigate and identify additional social media accounts and websites linked to this activity. For example, we have identified multiple Arabic-language, Middle East-focused sites that appear to be part of this broader operation that we do not address here. We use the term “inauthentic” to describe sites that are not transparent in their origins and affiliations, undertake concerted efforts to mask these origins, and often use false social media personas to promote their content. The content published on the various websites consists of a mix of both original content and news articles appropriated, and sometimes altered, from other sources.

Who Is Conducting This Activity and Why? Based on an investigation by FireEye Intelligence’s Information Operations analysis team, we assess with moderate confidence that this activity originates from Iranian actors. This assessment is based on a combination of indicators including site registration data and the linking of social media accounts to Iranian phone numbers, as well as the promotion of content consistent with Iranian political interests. For example: • Registrant emails for two inauthentic news sites included in this activity, ‘Liberty Front Press’ and ‘Instituto Manquehue,’ are associated with advertisements for website designers in Tehran and with the Iran-based site gahvare[.]com, respectively. • We have identified multiple Twitter accounts directly affiliated with the sites, as well as other associated Twitter accounts, that are linked to phone numbers with the +98 Iranian country code. • We have observed inauthentic social media personas, masquerading as American liberals supportive of U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders, heavily promoting Quds Day, a holiday established by Iran in 1979 to express support for Palestinians and opposition to Israel. We limit our assessment regarding Iranian origins to moderate confidence because influence operations, by their very nature, are intended to deceive by mimicking legitimate online activity as closely as possible. While highly unlikely given the evidence we have identified, some possibility nonetheless remains that the activity could originate from elsewhere, was designed for alternative purposes, or includes some small percentage of authentic online behavior. We do not currently possess additional visibility into the specific actors, organizations, or entities behind this activity. Although the Iran-linked APT35 (Newscaster) has previously used inauthentic news sites and social media accounts to facilitate espionage, we have not observed any links to APT35. Broadly speaking, the intent behind this activity appears to be to promote Iranian political interests, including anti-Saudi, anti-Israeli, and pro-Palestinian themes, as well as to promote support for specific U.S. policies favorable to Iran, such as the U.S.-Iran nuclear deal (JCPOA). In the context of the U.S.-focused activity, this also includes significant anti-Trump messaging and the alignment of social media personas with an American liberal identity. However, it is important to note that the activity does not appear to have been specifically designed to influence the 2018 US midterm elections, as it extends well beyond US audiences and US politics.

Conclusion The activity we have uncovered highlights that multiple actors continue to engage in and experiment with online, social media-driven influence operations as a means of shaping political discourse. These operations extend well beyond those conducted by Russia, which has often been the focus of research into information operations over recent years. Our investigation also illustrates how the threat posed by such influence operations continues to evolve, and how similar influence tactics can be deployed irrespective of the particular political or ideological goals being pursued.

Network of Social Media Accounts Impersonates U.S. Political Candidates, Leverages U.S. and Israeli Media in Support of Iranian Interests May 28, 2019 | by Alice Revelli, Lee Foster

In August 2018, FireEye Threat Intelligence released a report exposing what we assessed to be an Iranian influence operation leveraging networks of inauthentic news sites and social media accounts aimed at audiences around the world. We identified inauthentic social media accounts posing as everyday Americans that were used to promote content from inauthentic news sites such as Liberty Front Press (LFP), US Journal, and Real Progressive Front. We also noted a then-recent shift in branding for some accounts that had previously self-affiliated with LFP; in July 2018, the accounts dropped their LFP branding and adopted personas aligned with progressive political movements in the U.S. Since then, we have continued to investigate and report on the operation to our intelligence customers, detailing the activity of dozens of additional sites and hundreds of additional social media accounts.

The accounts, most of which were created between April 2018 and March 2019, used profile pictures appropriated from various online sources, including, but not limited to, photographs of individuals on social media with the same first names as the personas. As with some of the accounts that we identified to be of Iranian origin last August, some of these new accounts self-described as activists, correspondents, or “free journalist[s]” in their user descriptions. Some accounts posing as journalists claimed to belong to specific news organizations, although we have been unable to identify individuals belonging to those news organizations with those names.

Some Twitter accounts in the network impersonated political candidates that ran for House of Representatives seats in the 2018 U.S. congressional midterms. These accounts appropriated the candidates’ photographs and, in some cases, plagiarized tweets from the real individuals’ accounts. For example, the account @livengood_marla impersonated Marla Livengood, a 2018 candidate for California’s 9th Congressional District

SELECT COMMITTEE ON INTELLIGENCE UNITED STATES SENATE, VOLUME 2: RUSSIA'S USE OF SOCIAL MEDIA

Russian Social Media Tactics (page 15-16 from above)

Although the tactics employed by Russia vary from one campaign to the next, there are several consistent themes in the Russian disinformation playbook.

High Volume and Multiple Channels.

Russian disinformation efforts tend to be wide-ranging in nature, in that they utilize any available vector for messaging, and'when they broadcast their messaging, they do so at an unremitting and constant tempo. Christopher Paul and Miriam Matthews from the RAND Corporation describe the Russian propaganda effort as a , "firehose of falsehood," because of its "incredibly large volumes," its "high numbers of channels and messages," and a "rapid, continuous, and repetitive" pace of activity. Russia disseminates - the disinformation calculated to achieve its objectives across a wide variety of online vehicles: "text, video, audio, and still imagery propagated via the internet, social media, satellite television and traditional radio and television broadcasting."62 One expert,Laura Rosenberger of the 1 German Marshall Fund, told the Committee that "[t]he Russian government and its proxies have infiltrated and utilized nearly every social media and online information platform-including Instagram, Reddit, YouTube, Tumblr, 4chan, 9GAG, and Pinterest."

The desired effect behind the high volume and repetition of messaging is a flooding of the information zone that leaves the target audience overwhelmed. Academic research _ suggests that an individual is more likely to recall and internalize the initial information they are exposed to on a divisive topic._ As RAND researchers have stated, "First impressions are very resilient."64 Because first imp~essions are so durable and resistant to replacement, being first to introduce narrative-shaping content into ~he information ecosystem is rewarded in the_ disinformation context.

Merging Overt and Covert Operations. The modem Russian disinformation playbook calls for illicitly obtaining information that has been hacked or stolen, and then weaponizing it by disseminating it into the public sphere. The most successful Russian operations blend covert hacking and dissemination operations, social media operations, and fake personas with more overt influence platforms like state-funded online media, including RT and Sputnik.

Speed. Speed is critical to Russia's use of disinformation. Online, themes and narratives. can be adapted and trained toward a target audience very quickly. This allows Russia to formulate and execute information operations with a velocity that far outpaces the responsivity of a formal decision-making loop in NATO, the United States, or any other western democracy.

For example, within hours of the downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 over Ukrain, Russian media had introduced a menu of conspiracy theories and false narratives to account for the plane's destruction, including an alleged assassination attempt against President Putin, a CIA plot, an onboard explosive, and the presence of a Ukrainian fighter jet in the area. Dutch investigators with the Joint Investigation Team determined later the plane was shot down by a surface-to-air missile fired from a Russia-provided weapon system used in separatist-held territory in Ukraine.

Use of Automated Accounts and Bots. The use of automated accounts on social media has allowed social media users to artificially amplify and increase the spread, or "virulence," of online content. Russia-backed operatives,exploited this automated accounts feature and worked to develop and refine their own bot capabilities for spreading disinformation faster and further across the social media landscape .. In January 2018, Twitter disclosed its security personnel assess that over 50,000 automated accounts linked to Russia were tweeting election-related content during the U.S. presidential campaign.

Social Media, Political Polarization, and Political Disinformation: A Review of the Scientific Literature Mar 21, 2018

The current relationship between social media; political polarization; and political “disinformation,” a term used to encompass a wide range of types of information about politics found online, including “fake news,” rumors, deliberately factually incorrect information, inadvertently factually incorrect information, politically slanted information, and “hyperpartisan” news.

Black Trolls Matter: Racial and Ideological Asymmetries in Social Media Disinformation

Our computational analysis of 5.2 million tweets by the Russian government-funded “troll farm” known as the Internet Research Agency sheds light on these possibilities. We find stark differences in the numbers of unique accounts and tweets originating from ostensibly liberal, conservative, and Black left-leaning individuals. But diverging from prior empirical accounts, we find racial presentation—specifically, presenting as a Black activist—to be the most effective predictor of disinformation engagement by far. Importantly, these results could only be detected once we disaggregated Black-presenting accounts from non-Black liberal accounts.

Diffusion of disinformation: How social media users respond to fake news and why

This study finds that most social media users in Singapore just ignore the fake news posts they come across on social media. They would only offer corrections when the issue is strongly relevant to them and to people with whom they share a strong and close interpersonal relationship.

WEAPONS OF MASS DISTRACTION: Foreign State-Sponsored Disinformation in the Digital Age

Introduction and contextual analysis

On July 12, 2014, viewers of Russia’s main state-run television station, Channel One, were shown a horrific story. That day, Channel One reporters interviewed a woman at a refugee camp near the Russian border, who claimed to witness a squad of Ukrainian soldiers nail a three-year-old boy to a post in her town square. The soldiers had tortured the boy to death over a period of hours, before tying his mother to the back of a tank and dragging her through the square. The false crucifixion story was but one example of Kremlin-backed disinformation deployed during Russia’s annexation of Crimea.

Yet the use of modern-day disinformation does not start and end with Russia. A growing number of states, in the pursuit of geopolitical ends, are leveraging digital tools and social media networks to spread narratives, distortions, and falsehoods to shape public perceptions and undermine trust in the truth. If there is one word that has come to define the technology giants and their impact on the world, it is “disruption.” The major technology and social media companies have disrupted industries ranging from media to advertising to retail. However, it is not just the traditional sectors that these technologies have upended. They have also disrupted another, more insidious trade – disinformation and propaganda. The proliferation of social media platforms has democratized the dissemination and consumption of information, thereby eroding traditional media hierarchies and undercutting claims of authority. The environment, therefore, is ripe for exploitation by bad actors. Today, states and individuals can easily spread disinformation at lightning speed and with potentially serious impact.

The messages conveyed through disinformation range from biased half-truths to conspiracy theories to outright lies. The intent is to manipulate popular opinion to sway policy or inhibit action by creating division and blurring the truth among the target population. Unfortunately, the most useful emotions to create such conditions – uncertainty, fear, and anger – are the very characteristics that increase the likelihood a message will go viral. Even when disinformation first appears on fringe sites outside of the mainstream media, mass coordinated action that takes advantage of platform business models reliant upon clicks and views helps ensure greater audience penetration. Bot networks consisting of fake profiles amplify the message and create the illusion of high activity and popularity across multiple platforms at once, gaming recommendation and rating algorithms.

Research shows that these techniques for spreading fake news are effective. On average, a false story reaches 1,500 people six times more quickly than a factual story. This is true of false stories about any topic, but stories about politics are the most likely to go viral. For all that has changed about disinformation and the ability to disseminate it, arguably the most important element has remained the same: the audience. No number of social media bots would be effective in spreading disinformation if the messages did not exploit fundamental human biases and behavior. People are not rational consumers of information. They seek swift, reassuring answers and messages that give them a sense of identity and belonging. The truth can be compromised when people believe and share information that adheres to their worldview. The problem of disinformation is therefore not one that can be solved through any single solution, whether psychological or technological. An effective response to this challenge requires understanding the converging factors of technology, media, and human behaviors. The following interdisciplinary review attempts to shed light on these converging factors, and the challenges and opportunities moving forward.

How do we define disinformation?

Several terms and frameworks have emerged to describe information that misleads, deceives, and polarizes. The most popular of these terms are misinformation and disinformation, and while they are sometimes used interchangeably, researchers agree they are separate and distinct.

-

Misinformation is generally understood as the inadvertent sharing of false information that is not intended to cause harm.

-

Disinformation, on the other hand, is widely defined as the purposeful dissemination of false information intended to mislead or harm.

What psychological factors drive vulnerabilities to disinformation and propaganda?

Disinformation succeeds, in part, because of psychological vulnerabilities in the way people consume and process information. Indeed, experts on a 2018 Newsgeist panel – a gathering of practitioners and thinkers from journalism, technology, and public policy – identified a number of psychological features that make disinformation so effective with audiences. These features include how disinformation plays to emotions and biases, simplifies difficult topics, allows the audience to feel as though they are exposing truths, and offers identity validation.11

The need to belong

A large body of research shows that people desire social belonging, such as inclusion within a community, and the resulting identity that accompanies such belonging.12 Indeed, the research indicates that this need for belonging is a fundamental human motivation that dictates most interpersonal behavior. These motivations play out in real time online, often with drastic effect. For better or worse, the internet and social media have facilitated the ability to seek out and find a community that contributes to a person’s sense of belonging. In particular, research shows that social media can provide positive psychosocial well-being, increase social capital, and even enable offline social interactions.

So how does this apply to the resonance of disinformation and propaganda? In their desire for social belonging, people are interested in consuming and sharing content that connects with their own experiences and gives shape to the identity and status they want to project.

Research shows that individuals depend on their social networks as trusted news sources and are more likely to share a post if it originates from a trusted friend. This can increase susceptibility to disinformation if one’s network is prone to sharing unverified or low-quality information.

Similar to cognitive closure, the literature has identified other cognitive biases that dictate how people

take in and interpret information to help them make sense of the world. For example, selective exposure leads people to prefer information that confirms their preexisting beliefs, while confirmation bias makes information consistent with one’s preexisting beliefs more persuasive.27 These biases interact with, and complement, two other types of bias: motivated reasoning and naïve realism. While confirmation bias leads individuals to seek information that fits their current beliefs, motivated reasoning is the tendency to apply higher scrutiny to unwelcome ideas that are inconsistent with one’s ideas or beliefs.29 In this way, people use motivated reasoning to further their quest for social identity and belonging.

Further entrenching the effects of these biases, the research shows that naïve realism plays animportant role during the intake and assessment of information. Naïve realism leads individuals to believe that their perception of reality is the only accurate view, and that those who disagree are simply uninformed or irrational.

Cognitive limitations in an online jungle

So how do these cognitive biases play out in the social media sphere? A 2016 study of news consumption on Facebook examined 376 million users and 920 news outlets to answer this question. They found that users tend to confine their attention to a limited set of pages, seeking out information that aligns with their views and creating polarized clusters of information sharing.

Analysis determined that users are more active in sharing unverified rumors than they are in later sharing that these rumors were either debunked or verified. The veracity of information therefore appears to matter little. A related study found that even after individuals were informed that a story had been misrepresented, more than a third still shared the story.

Doubling down online

Given the human motivations that drive online behavior, researchers contend that it is more likely that polarization exacerbates fake news, rather than fake news exacerbating polarization.

People’s propensity toward “us versus them” tribalism applies just as much to the information they consume.

What, then, can be done to reduce polarization online? The literature highlights a number of challenges.

In an effort to avoid echo chambers, some have advocated for increasing online communities’ exposure to different viewpoints. However, one study that attempted this approach found it to be not just ineffective, but counterproductive.40 The study identified a large sample of Democrats and Republicans on Twitter and offered financial incentives to follow a bot that exposed the participants to messages of opposing political ideologies. The results were surprising: Republicans who followed the liberal bot became substantially more conservative, while Democrats who followed the conservative bot became slightly more liberal.

Given this ingrained resistance to new ideas, can people change their minds? The jury is still out.

The ability of individuals to adjust their perceptions after being shown corrected information may vary based on their cognitive ability.44 One study, in which individuals were shown corrections to misinformation, found that individuals with low cognitive ability less frequently adjusted their viewpoints than those with high cognitive ability.45 A similar study showed that an audience’s level of cognitive activity is likely to predict the persistence of misinformation and effectiveness of a correction.

Fighting fire with fire

So, what strategies might work to counter disinformation? Recent research is more positive regarding potential approaches.

Similar to how a vaccine builds resistance to a virus, attitudinal inoculation warns people that they may be exposed to information that challenges their beliefs, before presenting a weakened example of the (mis)information and refuting it. This strategy can better inform, and even immunize, participants to similar misleading arguments in the future.64 When applied to public attitudes about climate change, an experiment that used attitudinal inoculation with a polarized audience found that climate misinformation was less effective when participants were inoculated to similar misinformation in advance.

As these combined strategies suggest, many of the same psychological factors that make humans susceptible to disinformation can also be used to defend against it. Repeating facts, offering solid evidence, preemptively warning about and debunking disinformation themes, and encouraging openness to differing viewpoints are all potential approaches for reducing vulnerabilities to disinformation.

A look at foreign state-sponsored disinformation and propaganda

As the adoption of new technology and social media platforms have spread globally, so too have government efforts to exploit these platforms for their own interests, at home and abroad. Russian attempts to influence the United States 2016 presidential election and the 2016 Brexit vote in the United Kingdom are two recent, high-profile examples.

Yet the use of disinformation extends well beyond Russian interference in the US and the UK. A University of Oxford study found evidence of organized disinformation campaigns in 48 countries in 2018, up from 28 the year prior.

Russia

A 2017 report by the US Director of National Intelligence concluded that Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered an influence campaign that combined covert cyber operations (hacking, troll farms, and bots) with overt actions (dissemination of disinformation by Russian-backed media) in an effort to undermine public trust in the electoral process and influence perceptions of the candidates.

The extent of this campaign was significant – thousands of Russian-backed human operatives and

automated bots created more than one million tweets and hundreds of thousands of Facebook and Instagram posts, while uploading more than 1,000 YouTube videos. The tweets garnered 288 million views and the Facebook posts reached 126 million US accounts.

Chinese influence and disinformation campaigns

In September 2018, a four-page advertisement sponsored by the state-owned China Daily ran in the Des Moines Register. The advertisement, mirroring an actual newspaper spread with journalistic articles, included a selection of pieces that touted the benefits of free trade for US farmers, the economic risks of China-US trade tensions, and President Xi’s long ties to the state of Iowa. Targeting an Iowa audience in the midst of China’s agricultural trade dispute with Trump – and during the midterm campaign season no less – made clear that China would not hesitate to try shaping the US political conversation.

China’s ban on western social media is a tacit acknowledgment of these platforms’ potential to influence Chinese citizens. Meanwhile, the CCP uses foreign platforms’ networks to spread state-sponsored advertisements in foreign countries, including the United States. Chinese entities are Facebook’s largest ad-buyers in Asia, even though Chinese citizens cannot use the platform.120 Some estimate Chinese buyers spent five billion dollars on Facebook ads in 2018, making them the second largest market after the United States. State-sponsored media ads, a small fraction of that total, mirror the CCP’s offline efforts to paint positive portrayals of the Chinese government and broader Chinese society. Furthermore, the CCP has established Facebook pages for its various state-run media outlets, where content highlighting Chinese successes is distributed and promoted through page followers and paid advertising.

Iranian influence and disinformation campaigns

Between August and October 2018, Facebook cracked down on two separate Iranian propaganda

campaigns, removing hundreds of Facebook and Instagram accounts, pages, and groups, some of which

dated back to 2011. The pages alone were followed by more than one million Facebook accounts.

North Korean influence and disinformation campaigns

Covert tactics have also been used extensively by North Korea. As of 2018, an estimated several hundred DPRK agents operate fake cyber accounts to influence online discourse in favor of the regime. Aimed at a South Korean audience, these agents have created accounts meant to appear South Korean in order to post pro-DPRK comments, blog posts, and videos. Pyongyang’s intent is twofold: to paint North Korea in a favorable light and to stoke division in South Korea.

Follow the Money

Facebook 2020 income 70.7 billion 98.5% from digital advertising, mostly on ads on Facebook and Instagram pages.

Twitter 3.7 billion 86% from ads